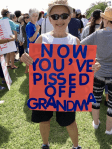

How angry tías, abuelas, and border residents are stepping up to help immigrants

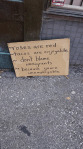

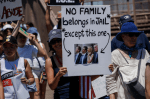

Tag: families belong together

Not gonna lie it bothers me that the anti-Trump demonstration in London is more than twice the size of the largest Families Belong Together protest. I know it was the weekend before a holiday but wHERE WAS EVERYONE???

I lost a follower right after I posted this.

Not gonna lie it bothers me that the anti-Trump demonstration in London is more than twice the size of the largest Families Belong Together protest. I know it was the weekend before a holiday but wHERE WAS EVERYONE???

‘I’ve never seen that before’: Activists marvel as calls for immigrant rights enter the mainstream

Maybe I’ll get back to this later, but I have an issue with the framing in this I can’t even start to articulate rn.

It’s a very pragmatic and calculated framing, but familiar. I talked about this on my last podcast. On one hand it’s great to see all these white people showing up, when say eight years ago, I’d go to an immigration protest and there’d be hardly any. On the other hand, what is that going to translate to? To really help immigrants and refugees in the here and now, we need to translate all this energy into policy proposals and successful bills and so on. If you’re a refugee family and you’re trying to get your mom into the US from somewhere like Dadaab none of this protest stuff means jack shit to you unless it produces a positive change in your life. And for that to happen, Democrats need to get back some degree of power AND there needs to be a concerted effort to make them keep their immigration promises. The fact that there are so many Democratic politicians with deep ties to immigrant communities makes this project possible, but it still can’t be ignored or taken for granted.

I can’t read the article because it’s behind a paywall but what you said on the podcast reminded me of when I went to a meeting about helping out undocumented people in my local community. There were a lot of immigration activists and faith leaders there. One thing that was emphasized repeatedly by the people who had been going to the meetings for years was that they were happy everyone was there (we were in an Elementary school classroom and it was so crowded that about half the people there couldn’t find seats) but disappointed that only a handful of people had been putting in the work during Obama. They also reiterated that White English speaking citizens needed to stay active in the fight and not disappear when there is a Democratic administration again.

‘I’ve never seen that before’: Activists marvel as calls for immigrant rights enter the mainstream

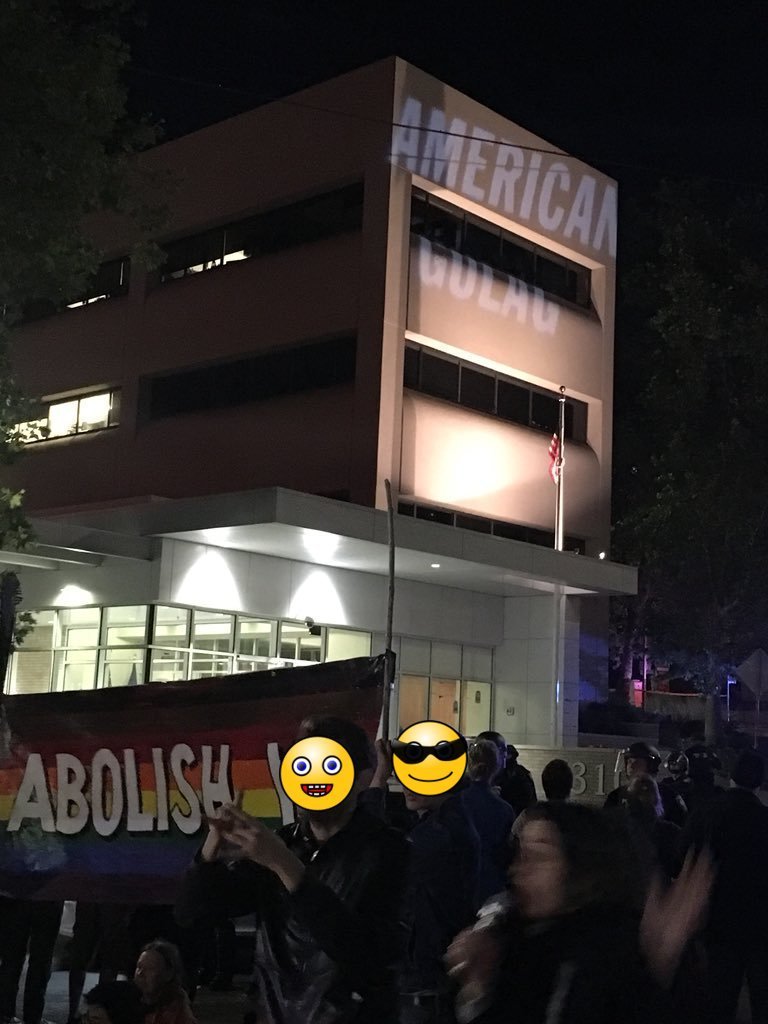

PORTLAND REPORTBACK! When DHS cleared the part of the camp that was blocking the ICE driveway here in Portland last Thursday, they hired a pressure washing company to come wash the chalk messages off the ground. The company showed up, realized they were, in a very tiny way, aiding ICE, and they walked off the job. And then they brought pizza back for the folks in the OccupyICE camp beside the building.

Did refusing to wash away those messages of “Abolish ICE” and “Families belong together” actually make a tangible difference for the currently separated families and the people currently facing deportation? No. But did it encourage and inspire us? Does seeing a company refuse service to ICE make it seem more possible for others to do the same? Yes, absolutely.So refuse to wash the ICE building. Refuse to sell tires to the transportation company that leases the buses to ICE. Refuse to operate the plane flying the children to the camps. Refuse to be part of the system. Don’t just “do your job,” follow your ethics and hang on to your humanity.

[source]

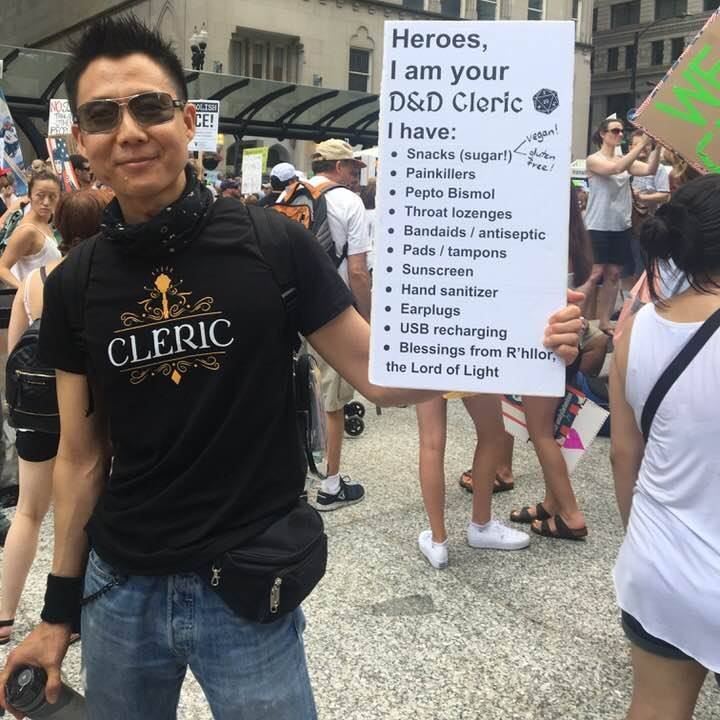

Been thinking a LOT about what modern hearthcraft looks like. The intersection of my practice and my politics. The celtic tradition of hospitality…

This person NAILS IT.

#goals

A Former Japanese Internment Camp Prisoner on the Dire Effects of Putting Kids in Detention

The government called it a “segregation center,” but Satsuki Ina calls it a prison camp.

Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941. The following February, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed an executive order authorizing the incarceration of anyone on the West coast who was deemed a threat, including everyone with Japanese ancestry. Government officials arrested Ina’s parents and took them to a horse track outside San Francisco that doubled as a temporary holding area. Ina’s family ultimately was sent to the Tule Lake Segregation Center near the California-Oregon border. Ina’s mother was pregnant at the time.

Tule Lake was a maximum-security prison camp that, at its peak, locked up over 18,000 people. Some 1,200 guards watched over the inmates from 28 watch towers. Some of the guards had machine guns. they were backed up by eight tanks.

“And that’s where I was born,” Ina told me.

Her father delivered a speech at Tule Lake at one point, declaring that it was his constitutional right to be free like other Americans. Ina says the U.S. charged him with sedition and punished him by separating the family and sending him to a prison camp in Bismarck, North Dakota.

By the time World War II ended, her family had been reunited at a prison camp in Crystal City, Texas. Ina was two and a half years old when she and her family were released. She says that time in detention has stayed with her, manifesting in longterm stress and negative physical consequences.

Today she’s a psychotherapist who has spent time visiting family detention centers, including the South Texas Family Residential Center, which sits just 44 miles away from her childhood prison in Crystal Lake.

Ina’s experience is eerily similar to what many young immigrants are experiencing today. I spoke to Ina about her life, work, and the longterm effects of detaining children in prison camps.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

You were born inside a prison camp here in the U.S. The U.S. government apologized for locking up Japanese-American families. What goes through your mind now when you hear the is U.S. detaining about 11,000 children in “shelters” across the country?

It’s alarming. It’s so resonant with what my family and my whole community had to experience. America made a horrible mistake back then.

When Pearl Harbor was attacked, there was so much collective anxiety in our country that finding a scapegoat was a natural outcome. The U.S. government just completely bypassed constitutional rights and human rights. And that’s that’s what I feel like is happening today with the inhumanity of separating children from their parents as a form of punishment.

I interviewed mothers in a family detention facility and I asked them why they would take such a huge risk and cross the continent to to get to the U.S. border. And it’s because they did not want to be separated from their children.

They worried that their daughter could be kidnapped and become part of sex trafficking or that their boy would be captured and become part of a gang. The women told me that they felt like they had to gather their children and escape so that they could keep their children from being separated from them.

What are some of the longterm effects that these children in detention may have to live with?

I am a psychotherapist, so I work with children who have been traumatized and what they are experiencing is definitely trauma. One of the worst traumas for children is to be separated from their caregivers and then placed in what they calling “temporary detention facilities.” But it’s indefinite detention—they have no idea how long they’re going to be held. They have no idea if they’ll ever see their parents again.

That level of anxiety causes tremendous emotional stress, and we know from the research in neuroscience that constant release of these stress hormones can affect a child’s ability to learn, a child’s ability to self-manage, to regulate themselves.

The longterm impact that I’ve seen in my own Japanese American community is this hyper-vigilance, this need to constantly prove themselves, and always being on edge. Japanese Americans are viewed often as the model minority but I see the behavior of needing to strive and not offend and belong and maybe give up their own personal aspirations to fit in has come at a great sacrifice and is a reaction to having been incarcerated unjustly.

You left the prison camp when you were two and half years old. How did those years affect you?

This kind of treatment has consequences for a lifetime for a child. The trauma effect is pretty severe when there’s been captivity trauma. We were unjustly incarcerated when we weren’t guilty of anything.

Today I live with anxiety about the possibility of random accusations or being blamed for something. That’s constantly present. So we are always working hard to please people and not cause trouble. There’s a constant need to be perfect. We don’t show up in the criminal justice system but we end up with a lot of psychosomatic disorders and symptoms resulting from over-achievement. We question our integrity and worthiness. I’m over-educated, for example. I have a Bachelors, Masters, PhD, I’m a licensed therapist, a certified gerontologist, the list goes on.

That high level of anxiety has given me high blood pressure. A lot of us who were incarcerated as children have high blood pressure. A study by Dr. Gwendolyn Jensen found that Japanese men who were detained had a 2.1 greater risk of cardiovascular disease, cardiovascular mortality, and premature death than Japanese men in Hawaii who were not imprisoned. [The study found the youngest detainees reported more post-traumatic stress symptoms and unexpected and disturbing flashback experiences.]

A Former Japanese Internment Camp Prisoner on the Dire Effects of Putting Kids in Detention